The Passionate Pantheon novels are set in a post-scarcity society 50k-100k years in the future, on a planet far from Earth. The books are written in English (blame the limitations of the authors!), but English is not the language of the City. So what is?

Language is a funny thing. Language is fluid; the English of Shakespeare is not the English of modern-day London, which is not the English of modern-day New York. And both would be incomprehensible to the creator(s?) of Beowulf. Those same transformations and developments have happened in every language.

In the universe of the Passionate Pantheon, the world of the City is a second-generation colony, settled with slower-than-light generation ships from a colony that was itself settled, slowly and painfully, by a generation ship from Earth.

The last people to leave Earth did so in a hurry. They arrived at their new home with little more than the shirts on their backs, and they came from every culture, society, and economic level on Earth. A lot, as you might imagine, was lost—including their native languages. That first generation ship set up a colony where people spoke a mishmash of many languages. In order to communicate, first they developed a pidgin, then as it became more complex and children grew up learning it, it turned naturally into a creole. It is from this creole that the language of the City arose.

So how did their language develop? What linguistic pathways led them there? And what does that language even sound like?

One of the foundational values of the world of the Passionate Pantheon is beauty. Beauty in the City is a fundamental virtue; the people of the City strive for beauty in everything they do, even in utilitarian things. And this, we think, would be reflected in their language as well.

The language of the City traces its roots back to a number of pan-Asian, African, and Indo-European languages. Some of the languages that went into this odd mashup were tonal, some were atonal. The resulting creole, which established itself as that first colony’s language, preserved the tonality of pan-Asian languages. (This is, in the real world, fairly unusual; most real-life pidgins and creoles, with a few exceptions like Singlish, tend to be atonal, even when they form at the intersection of tonal languages.)

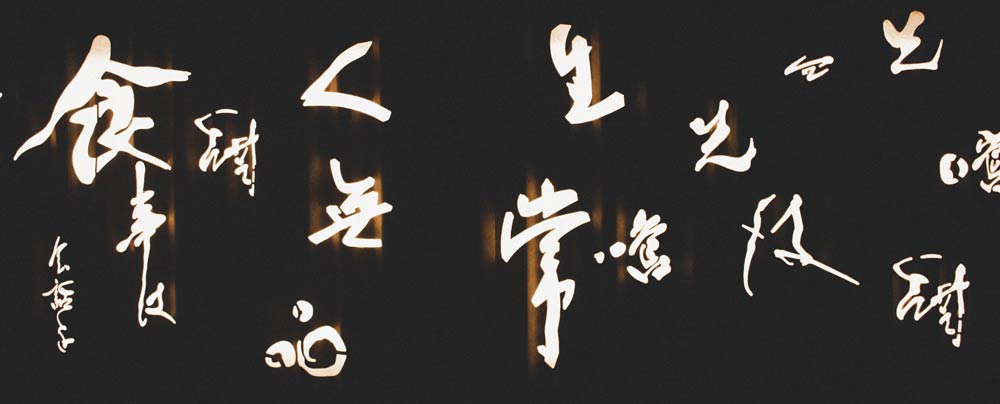

The second colony, the world of the Passionate Pantheon, kept the tonality and enhanced it; the love of beauty expressed itself in the language as a musicality. (Their written language is just as beautiful, and quite complex—more on that later!)

To a person from the real world, the language of the City probably sounds quite musical; ordinary conversations about what to have for dinner might sound to our ears like poetry, and poetry like singing. Actual singing would be almost unbearably lovely.

We’ve spent quite a lot of time talking and thinking about what the language of the City is like, and looking for rough approximations that might give some sense to a native English speaker about what it might sound like—with, alas, limited success. The closest thing we’ve found so far is traditional folk singing like “Эрбэд соохор” (Erbed Sookhor) from the Republic of Buryatia, and even that is only the crudest of approximations.

We say “the language of the City,” but that’s not entirely accurate. There are many Cities in the world of the Passionate Pantheon, each one largely isolated from the others, with little cross-communication. As a result, each City has developed its own dialect—intelligible to the inhabitants of every other City, but still recognizably unique.

The language is both complicated and simplified by the gods. The various AIs that are worshipped as gods in each City do communicate with each other, and the language of the City, as much as it has evolved naturally, is still influenced by the AIs. This influence traces its roots all the way back to the first generation ships; their simple AIs weren’t regarded as gods, but they learnt and then later helped shape the language that evolved from the initial pidgin and the creole that rose out of it. Even the early AIs had a deep love of beauty, and particularly loved music, as it’s possibly the most mathematical form of artistic expression, so they steered the new evolving language in the direction of musicality.

The connection between the AIs of the various Cities enables them to prevent the languages of the different Cities from varying too much, though there are still local variations. The language is more complex in Cities where the Lady, the god of creation and beauty, is more important, since poets, musicians and storytellers tend to play with language and song. This tends to be less significant in cities where worship of the Lady is less important, such as the City of the second novel, Divine Burdens.

In Divine Burdens, we meet people who have lived in the Wastelands all their lives, rather than living in a City at all; their language is markedly different from, and quite a lot less complex than, the language of the City. Their dialogue uses a very different cadence and vernacular.

“Us?” Gavot said. “We didn’t bring you here. You came here your ownself. Why were you exiled, hmm, Rajja of the City?”

Rajja remained silent.

“Aha! You see? It was your own hand set you on this path. The gods guided you here. And now they have given you to us, you wise? You have been delivered to us, and we will take you! Don’t you fear, now. We would not harm such a gift.”

The man in the back, Kendon, touched a spot on the floating box. It settled to the ground. The other four men gathered around the net.

“Do you surmise she’ll fuss?” Taín said.

“Ach, they always fuss, I keen,” Gavot said.

From Divine Burdens

The people of the City live very long lives, and have a lot of time to explore language and expression. People who live in the Wastelands tend not to live as long, and don’t have access to Providers to tend to their every need. Their lives are more focused on survival as a result. We see this pattern in real languages: cultures which developed in lush, fertile areas and therefore aren’t as focused on mere survival tend to create languages that are richer and more complex than people who live in harsh environments that force them to focus on survival.

The result of all this is a language that melds many of the structures of languages in the real world, but adds an element of musicality driven by a deep, foundational love of beauty for its own sake, with an extremely complex syntax and grammar shaped in part by intelligences much greater than human.

To a person from the real world, the language of the City would sound quite beautiful but also be so complex as to be impenetrable; it would likely be quite difficult for an adult from the real world to learn. From the perspective of the City, the languages of modern-day Earth might sound quite harsh and clumsy, simple in their structure, distinctly un-musical, and lacking in nuance.

In some ways, the people of the Passionate Pantheon books are a bit like a more playful version of the fey of mythology. (More on that later, too!) They are still human, but their culture, and their language, is quite alien from our perspective. There’s a limit to how well we can communicate that in an English-language novel, though we’re getting better as we go—the third novel, The Hallowed Covenant, presents quite a bit more of the culture and society of the City. The novels still don’t capture all the layers of the language of the City—there are multiple formal and informal modes of speaking that don’t exist in English, for example, and the modes might indicate the type of relationship between two people, the hierarchy that exists between them, and the history they share. On top of that, in the City of The Hallowed Covenant, where the Lady is a primary god, there are modes of syntax and grammar used exclusively by poets and storytellers, whereas the City of the fourth novel has extremely complex modes of grammar between people of different status in the City’s hierarchy.

Of course, we’re making the people of the City sound like they’re beautiful and ethereal and distant—unrecognisable as humans, in other words. The truth is, they love a good meme or colloquialism or bit of slang in the same way that humans throughout history have always done. They like wordplay and puns, they enjoy making up clever vernacular…they like playing with their language in a way, say, Tolkien’s elves maybe don’t.

In a lot of ways, our intention with the Passionate Pantheon novels is to show what might happen if you take a human society and turn the knobs on some of the traits up to eleven. One of those traits is our human tendency to communicate in many varied (and occasionally unnecessarily complicated!) ways. Language is one of the jewels in the crown of what it means to be human, and it’s a shame that we will never be able to fully convey the extent to which it has developed in the City.