We haven’t updated the blog in a while, as we’ve been completely buried under other writing projects. However, a question came up on another site recently about inventing an entirely new language for fiction. Since this is something that’s on our minds right now—we’re about a third away through wirting the fifth Passionate Pantheon book, in which psycholinguistics plays a key role (the protagonist is interested in linguistics and anthropology), we thought it might be appropriate here.

Do you need to worry about coming up with an entire new language for your fantasy or science fiction world? You can, sure, if you’re a linguist, or a conlanger, or someone else with an interest in language.

Should you do this? For the most part, your audience probably won’t care.

I think it’s good to know how the language in your setting works. Language is important. But unless you’re JRR Tolkien, who wrote his stories essentially (at least at first) as a way to give the languages he invented a context and a history, every moment you spend creating a language is a moment you, well, aren’t writing.

Now, Eunice and I are both language nerds, so we know a huge amount about the language of the City in the Passionate Pantheon novels…most of which will never appear in the novels themselves.

For example, we know the language is tonal. We know the language started as a pidgin of several pan-Asian languages thousands of years ago. We know that in the time the novel is set, there are no extant Romance or Romance-derived languages left.

Eunice invented a brilliant writing system for the language fo the City. It’s both phonetic and ideographic; the language has thousands of written symbols, each of which represents a word, and each of which also represents a sound. Since the number of ideographs is far larger than the number of phonemes, each spoken sound can be represented by one of hundreds of different ideographs.

So a piece of text can be read two ways: phonetically or ideographically, with the ideographs that are used to spell each word informing the meaning of the word.

That means you can write a piece of text ideographically, like Chinese. Or you can also write it phonetically, with any given word spelled in literally hundreds or thousands of different ways.

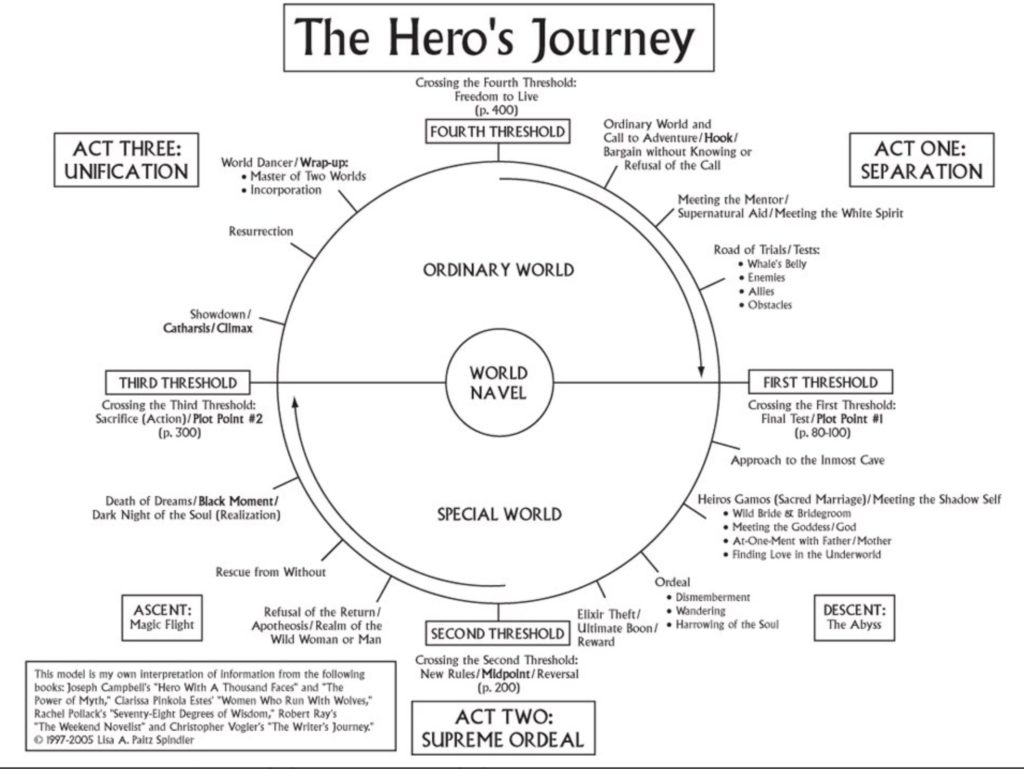

Eunice also invented a completely brilliant, breathtakingly beautiful system for teaching children to read and write: “story wheels.” These are short fables or parables, written phonetically in circles with each line of the fable written like the spokes of a wheel. Children play a game where they change the meaning of the story by changing the characters that spell each phonetic word, so the phonetic words retain the same meaning and pronunciation but the context changes.

Some information about the language does appear in the books, where it’s relevant. For example, the protagonist in the fifth book is fascinated by language, history, and anthropology, and that’s part of the book’s plot. (In one scene, she gets distracted on her way to a sex party by a conversation on anthropology, because who among us hasn’t had that experience, amirite?)

There’s a scene in the book where she plays a game with her childhood drone on the evening before she takes her first adult name, and loses her drone forever:

The drone accompanied her to her room, where it hovered silently as if it didn’t know what to say. She sat on the edge of the bed with her knees drawn up to her chest. At last it said, “Would you like to go to sleep?”

“No,” she said. “After tomorrow, I’ll still be able to see my parents, but I will never see you again. I would like to spend a last few moments with you.”

The drone bobbed up and down in a nod. “What would you like to do, little mouse?”

“I want—” She stopped herself from saying I want things to be different. I want this not to be the end. The unspoken words hung heavy between them. “I want to spend time with you.”

On an unseen signal from the drone, the lights dimmed. The projector in the drone’s nose glowed. A circle floated in the air in front of it, divided into sectors by glowing green lines, every sector filled with graceful calligraphy. She leaned forward. “I haven’t seen this one before.”

“It’s a new story I’ve been working on,” the drone said “I call it The Stars that Sang.”

“Were you thinking of me when you wrote it?”

“Yes.” The drone dipped. “Do you want to play?”

“Yes!” She studied the wheel for a while, reading the flowing script over and over. “Okay. Fourth line, change the spelling of ‘space’ from ‘vast lonely deep despair’ to…um…” She frowned in thought. “‘Open heavenly wide distant.’”

“Mm, interesting,” the drone said. The floating wheel changed, the calligraphic characters rippling into new shapes. “I’m surprised you didn’t start with line two, ‘night.’”

She shook her head. “Too obvious.”

“Okay, now you’ve changed the sentiment of the opening, where do you go from here? You’ve taken away the emotional contrast between the opening and the closing.”

“Hang on, I’m not done yet!” She stuck her tongue out at the drone. “Line seven. Change the spelling of ‘silent’ from ‘calm peaceful waiting sunset together’ to ‘heart hangs awkward tense breathless.’”

The glyphs changed. The drone tilted sideways, considering the new story. “You’ve left the story the same but changed the meaning entirely.”

She rubbed her hands together. “I’m just getting started. Eighth quadrant. What if we change the spelling of ‘music’ from ‘sweet light joyous exultation soaring’ to ‘sweet sorrow regret past haunting’?”

They stayed up until well into the night, writing and rewriting the drone’s story, until by the time her eyes grew heavy it had changed in meaning many times even though the words remained essentially the same. Eventually, she crawled beneath the covers, still fully dressed. The drone pulled the covers over her with a set of long, jointed manipulators that unfolded from its body. “Sweet dreams, little mouse,” it said.

“It still sucks,” she said.

“I know.”

But as for actually making the language? To the extent someone might speak or write it? Oh hell no. Only one tiny fragment of the language exists:

She stared at the night sky for a while, watching the stars twinkle beyond the shield. The larger moon glowed through wispy clouds just above the wall. After a time, she said, “Will you sing me a song?”

“Of course. What would you like to hear?”

“Sing me the song about the mouse in the moonlight.”

The drone floated higher. “As you wish.” Its voice changed, softening, becoming deeper as it sang.

Lahr Airiîthnē, na elerē, hauieira so vanawya elle

Lahr Airiîthnē, ye olowē, ramatriyá allanyo té hwell

Fandirhî håo on kyio noyinniara

Ran Apla, ye Apla, in méie jhonaíra

Lahr Airiîthnē, na elerē, vanasaya etra tun nos esserentiáliaShe closed her eyes as the song unfolded, pretending for just a moment that her naming ceremony was still off in some distant future, with endless days of play still stretching out before her. As the drone sang, she pictured the story wheel behind her eyes, the lines of the story arranged like spokes, each line both a word and a sentence.

The drone’s voice faded away at the end of the song. Tears leaked from the corners of her eyes. “It’s not right,” she said.

“Right does not mean painless. This is necessary,” the drone said. “The little mouse has grown into a strong, beautiful person. I came to you to help guide you to this place. Now your path is entirely up to you. It’s time for you to step into yourself.”

We know enough about what the language sounds like, and the rules that are used to put words together, to do that much, but no way in hell are we ever going to create a whole language!