What do you think of when you hear the word ‘faery’? Is the first thing that pops into your head a dainty, cherubic creature with translucent wings at the bottom of the garden, or do you imagine the old fey, the dangerous fey, the fey of myth and legend who use glamour and sorcery to ensnare, the shapeshifting fey you never bargain with unless you’re very careful indeed (and make sure to count your fingers after)?

We were midway into writing the fourth book of the Passionate Pantheon series when Eunice observed that the citizens of the City are, in a way, far-future fey. But here, we see them through their own eyes, from the inside, rather than (as is the case with most fairy tales) from the outside looking in. The residents of the City are humans, to be sure, but humans who have grown up in a society so alien to ours it looks a lot like the fey from those ancient, cautionary tales.

You might not instantly see the connection between far-future, post-scarcity science fiction erotica and that old European folklore. But consider the elements often present in tales of the fey folk, and you’ll find some startling similarities.

This might be inevitable. Fairy tales are among the oldest stories in human existence, many of them dating back 6,000 years or more. And like with all stories of strange and alien beings, they’re really a way of looking at ourselves.

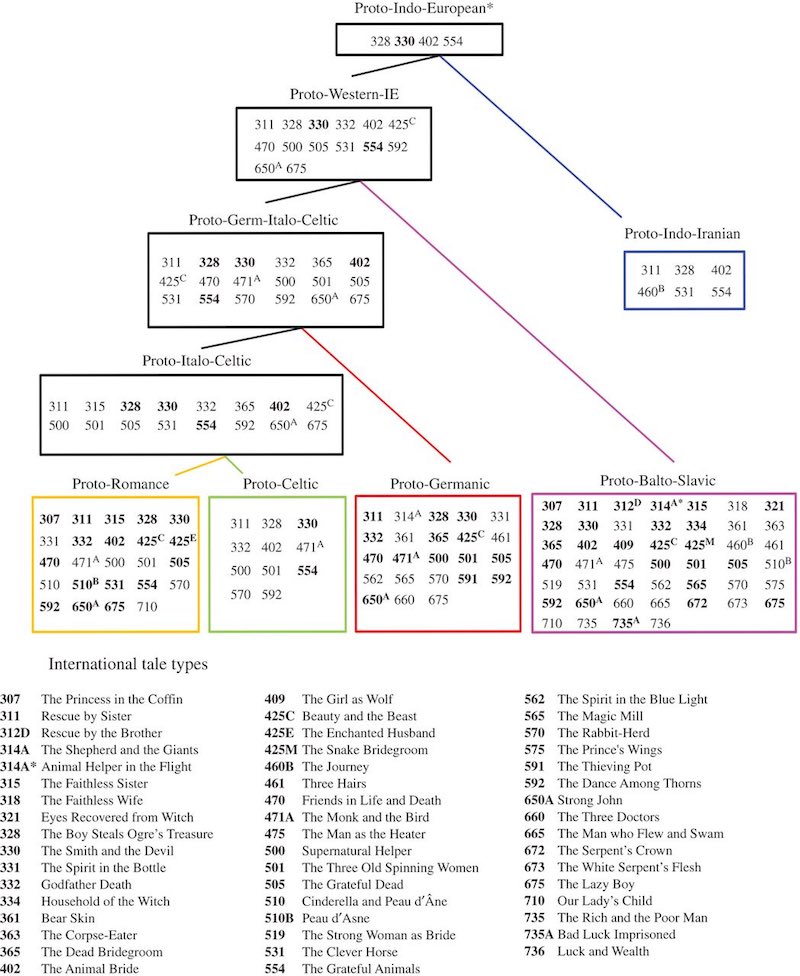

Linguists and scholars have built a phylogenetic tree of fairytales that extends back to the Bronze Age, 6,000 years ago:

There’s an incredibly long history to fairytales. They’ve been used to teach cultural mores through the magic of fiction since the dawn of storytelling. And most importantly, they’re a way of looking at ourselves in a different light, of asking “what if?” questions about human nature.

And really, isn’t that what science fiction is for?

So let’s think about the fey in terms of the Passionate Pantheon stories. What are the fey?

“Elves are wonderful. They provoke wonder.

Elves are marvellous. They cause marvels.

Elves are fantastic. They create fantasies.

Elves are glamorous. They project glamour.

Elves are enchanting. They weave enchantment.

Elves are terrific. They beget terror.

The thing about words is that meanings can twist just like a snake, and if you want to find snakes look for them behind words that have changed their meaning.

No one ever said elves are nice.”

― Terry Pratchett, Lords and Ladies

In many of the old tales, the fey have a consistent set of qualities. The fey are strong, long-lived, alien beings who love beauty, work magic, project glamour, change their form, have a peculiar and refined hedonism, and are very exacting with their language. They don’t break promises (but are extremely careful of their wording!) and they see power in names.

Sound familiar?

If you’re not seeing it yet then hang on to your bustle, we’re about to let this genie out of the bottle (literary archetype 331)!

Firstly, their longevity. The citizens of the City live a very long time—centuries, typically; many centuries, if they choose. They almost never die until they choose to. The fact they use biomedical nanotechnology and medical pods to do it, rather than magic, is simply a detail; the fact is, the characters you’ll meet in the City are old, sometimes very old.

They continued on their way again, walking for a while in silence. The small raft drifted past, nudged along by the unhurried stream. Finally, Jakalva said, “How old are you?”

“Sixty-seven.”

“Ah. You’re young, then.”

Kaytin hung her head. “Is that bad?”

“We all start out that way.”

“How old are you?”

Jakalva laughed, but an edge of sadness underlaid it. For the first time in Kaytin’s experience, she looked tired. “I have lived nearly ten of your lifetimes.”

—From Book Four, tentatively titled Unyielding Devotions

The amount of experience one can gain over such a long life leads to its own form of otherworldliness, and an associated way of thinking about time that is very different from ours. With all that time to explore and experiment, would it be so surprising for someone to develop a desire for new experiences that we would consider extreme or intense? We discussed this in more depth in our earlier blog post Some Musings on Consent, Part 3. In those old stories of the fey, they are often shown playing with their human playmates in ways that we would consider cruel or mischievous. What if, like the residents of the City, those fey have merely developed a taste for novelty over the long span of their lives?

“Okay, let me try to explain,” Lanissae said. “It’s…” She paused, regarding Kaytin through hooded eyes. “I like…I like the tiny spaces. I like that little moment of clarity that happens when you switch, you see? There’s that one second when you know what’s going to happen. You see it in their eyes. You know that when that second is over, they will want you so badly that nothing you can do will stop them.” She shivered, eyes half-closed, and slipped one hand inside the plunging neckline of her shimmering, lacy dress. “Mmm. To be seen with such desire, to know that when the moment passes you will not want it and would do anything to make it stop, to know that it will happen anyway…there’s a delicious inevitability to it.” She cupped her breast. Her eyelids fluttered. “It’s such an exquisite surrender. You exist only to be ravished.” She exhaled in a soft moan. “You can’t get away. You lose yourself in how much you don’t want it, but it doesn’t matter. You stand on the brink and for one instant, you see it all so clearly, and you know what’s about to happen, and you also know that you chose to be here. You walked into the cage yourself, of your own free will…oh!” She leaned back on the couch and caressed her nipple beneath her thin dress.

Kaytin stared at her with a mixture of desire and revulsion roiling within her. “And then,” Lanissae went on, “the violation is over, and the change happens, and you have that moment of clarity again. You feel the heat in your body. For that one delicious second, you know. When the heat reaches your head, the need will take you, and nothing in the world will matter except the person you are about to ravish. Everything stops. You balance on that edge. You recognize each other. You see the humanity there. In that instant, you share a connection that’s absolutely magical. For that one brief second, you see each other, really see each other—not as predator and prey, but as two people sharing an experience. You know that when the moment passes, you will not be able to stop yourself any more than you could stop what was coming when you were the object. You can feel your mind going…mmm.” She caressed her neck with her fingertips. “You embrace that moment of humanity, before it all slips away. It’s…uh! It’s so magnificent to stand on that cliff and feel yourself about to fall.” Lanissae arched languidly, running both hands down her arms. “When I’m in the cage, I live for those moments of connection between the moments of madness.”

—from Book Four, Unyielding Devotions

Of course, unlike the people of the Passionate Pantheon (who are extremely careful about consent), the fey have forgotten (or do not care) that the humans they play with do not share their tastes, or their resilience. One thing that enables that unbounded exploration in both cases is that residents of the City, like the fey, are physically resilient. Again, this being a consequence of their technology doesn’t change the reality: they can shrug off things that would be permanently disabling or even fatal to people without their technology (or magic, for the fey).

“So, um, are you a worshipper of the Blind?” Kaytin asked. The table went still for a moment. Both of Fyli’s drones swiveled toward her. Kaytin blushed. “I’m sorry! Did I say the wrong thing?”

Fyli shook her head. “No, it’s fine. And to answer your question, I worship the Wild.” The jeweled drones drifted farther up, spreading out as they did. Kaytin found herself pinned beneath their gaze. “I went float-field diving off the top of Tower Four a while back. Misjudged a thermal and slammed into the side of the tower. Broke my nose, tore up my face. Ripped my wingsuit, too. I went into the float field too fast and broke both legs when I hit the ground. A drone carried me to a medical pod. I couldn’t see, so it loaned me its eyes while it carried me. I found the experience…enlightening.” She grinned, exposing pointed teeth. “Drones see better than we do. Later on, I traded my eyes for these. I’d rather see the world this way. Normal eyes can’t compare.”

—from Book Four, Unyielding Devotions

This brings up another similarity: the residents of the City can change their form in almost any way they choose. Whatever you want to look like, if you can describe it adequately to a medical pod, you can do it (although unlike the fey with their glamours, the residents of the City are, of course, still subject to the laws of physics and biology.)

A turbulent river of people in brilliant, colorful clothes or, often, body paint flowed around them. They passed a tall pale-skinned woman with emerald eyes, nude but for a complex pattern of red lines painted on her body, juggling a dozen small, brightly glowing spheres that left trails in the air behind them. Lyrin stepped out of her way and backed into a man half again as tall as he was, towering head, shoulders, and chest above the crowd. Light gray fur covered his skin. Two great wings, feathered in brilliant white, sprouted from his shoulders. “Sorry,” Lyrin said.

“My fault.” The man spread his wings wide. “This body takes up a lot of space.”

Yaeris looked him up and down. “Can you—”

“Fly?” He laughed. “I wish. They sure are pretty though, aren’t they?”

A sylphlike woman with skin of purest white and eyes of deep scarlet walked between them wearing nothing at all. In place of hair, she had a nest of long, slender snakes that curled and writhed, each a different color. Their scales glittered in the sun. She gave Yaeris a long, appraising look before she continued on her way.

—from Book Three, The Hallowed Covenant

One consistent feature of the physical changes we just mentioned is that those bodies are all designed to be beautiful. Those who live in the City love beauty in all things, and what better place to display that than through their own physical form?

Every object in the City, even the most mundane, is designed to be beautiful—even if it’s only temporary, destined to be tossed into a Provider to be torn apart for its constituent molecules as soon as it’s served its function.

“Thank you for your hospitality.” She presented Avia with a small, glittering box made of thin plates of gold, edged with polished wood and inlaid with bands of copper, silver, cobalt, and platinum. “For you.”

Avia picked up the gold box. A tiny confection, barely as wide as her thumb, nestled on a small cushion inside. It was shaped like a dome, and built of many layers of different colors: pink, white, red, blue, and brown. A thin, glittering band separated the layers. A round berry rested on top. Avia placed it in her mouth. A complex mixture of tastes, sweet and tart and spicy, flitted across her tongue. She swallowed.

The sensation started as a warm gentle glow that enveloped her body. She felt a faint whisper against her skin, like a hand caressing her shoulders. A shiver ran down her back. She felt something warm and soft, like fine fur, wrap itself around her. A cool breeze touched her face, bringing with it the faint scent of pine trees and flowers. The wind passed, the feeling of fur against her body faded, and the faintest whisper touched her lips, like the ghost of a kiss. “Mm, that was lovely,” she said when the sensations faded. “I like the kiss at the end. What a wonderful touch.”

“Thank you,” Tikil said.

Avia dropped the box into the Provider. Its edges flared blue as it disintegrated into dust. The black rectangle flipped closed.

—from Book Three, The Hallowed Covenant

Their ideals of beauty may not be the same as ours, of course; not many people in modern-day society would find Euralye a model for physical beauty! But alien as their standards may sometimes be, the characters of the Passionate Pantheon love beauty.

Now, you may be thinking “What about magic? Fey have magic, it’s practically their main characteristic!” And it’s true that a common factor in every fairy tale analyzed by linguists and historians is magic. But what is magic, but the ability to change the world to your desire? The ability to heal almost instantly, to change your form at will, to call up whatever you want whenever you want it? All this looks, to us, a lot like magic. Arthur C. Clarke famously said “Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.” The tech in the Passionate Pantheon allows people access to abilities that seem magical.

They met back up with the others near the ruins. All three of the other candidates sported new collections of bruises and welts. “This is not an ordinary forest,” Ortin said. “This forest is an extension of the God of the Hunt, and he controls everything in it. Listen. What do you hear?”

Lija listened. Far in the distance, she heard the cry of birds. Nothing seemed out of place. “Birds,” she said. “The wind in the trees. The stream by the ruin.”

“Where are the birds?” Ortin said.

“That way.” Lija pointed.

“What else?”

“Nothing.”

“Exactly.”

“I don’t understand,” Marel said.

“Listen to what’s close,” Ortin explained. “Do you hear any birds?”

“No.”

“The forest grows silent wherever the Hunted walks,” Ortin said. “You can track by what isn’t there as much as what is. If you are a Hunter, use that to your advantage. Hunt by the voids in the sounds of the forest. If you are Hunted, remember that silence is a giveaway. Keep close, as much as you can, to natural sources of noise. Cover your silence as you would cover your tracks.”

—from Book Two, Divine Burdens

Another major aspect that everyone knows about the fey is that you don’t give them your name. Names are power, and to give a fey your name is to give it power over you. Names in the Passionate Pantheon also hold tremendous power, if in a very different way. People choose their own names when they reach adulthood. They select a public name, by which they are known to the rest of the City, and a private name, which they share—if they ever share it at all!—only with their most intimate partners. One of the greatest taboos of the City, and almost the only taboo which will cause the gods to intervene directly in ways that would typically require the consent of the offender, is revealing another person’s private name without permission. To know something’s true name is to have power over that thing.

A veiled Confessor removed the ribbon from her eyes. The vast hall of the Confessory came back into focus. She felt the soft pillow under her knees, smelled the sweet smoke curling up from the censer. Her skin glowed. She looked down. Loops and designs in black ink covered her skin. Thin straight welts crisscrossed her body.

The Confessors lifted her from the cushion. They carried her to the transparent tub, where the four of them bathed her with great care. The sponges, rough on her skin, sent flurries of pleasure rippling all the way down to her toes. She moaned softly. When they finished, she stood and allowed them to dry her. One of the Confessors unbound Sayi’s wrists and handed her the ribbon.

The four of them lifted Sayi and placed her back in the chair. She shivered with pleasure as her ass sank into the soft cushion. She wound the ribbon into a tight coil and presented it to Tashaka. “Burn this during your ceremony, just before you exchange your private names, to receive the blessing of the Keeper.”

—from Book Three, The Hallowed Covenant

Finally, the people of the City, in very fey style, take promises and oaths very seriously. Breaking a promise is a huge offense, and telling a falsehood is cause for prompt consequences. The people of the City are expected at all times to speak only the truth. The gods, through the drones, watch them constantly (more on that in a later blog post!), so getting away with an untruth or a broken promise is virtually impossible.

“I can’t do service, I just can’t!” Tessia wailed.

Penril sighed. “When we created the first gods,” he said, “we struck a pact. The gods would provide for us, and in exchange, we would worship them. Central to this covenant is the idea that a promise is a sacred thing. Nobody, human or god, may break a promise once given. To do so is to tear at the foundation of our society.”

“But I—”

“I’m not finished!” Penril thundered. “If we cannot count on one another to keep our promises, the bonds that tie us to each other in mutual cooperation fail. All of society crumbles. A promise, whether to a person or to a god, is a bond. If you break that bond, what place do you have among civilized people?”

Tessia wept, wracking sobs that shook her slender frame. “I know!” she said. “I can’t—I just—I didn’t know! I thought I could do it! I’m sorry!”

Penril’s gaze held steady. “You have made a promise to the Blesser and to me. You made your promise in the presence of Avia in her role as Vessel of the Blesser. Keeping your promise is not optional. I will expect you to be here half an hour before sundown in four days’ time, prepared to serve the Blesser.”

—from Book Three, The Hallowed Covenant

Of course, whilst they are expected to keep promises to the letter, and to say only that which is truthful, there is nothing stopping them from using objective truth to be a bit misleading. Like the fey, they can be very precise with their choice of wording.

It took a while for us to notice that the Passionate Pantheon novels are science fiction fairy tales because in most fairy stories, we see the fey from the outside, through a glass darkly. They’re intended to illuminate the human condition through contrast.

With the Passionate Pantheon books, we see the City through the eyes of its residents, not from the outside. Our novels show us the fey as they see themselves, not as humans see them. (The City’s people may be human, but their language, technology, and culture have changed them immeasurably; in a myriad of subtle ways, they’re more alien to us than we are to, say, an ancient Roman Centurion.)

Eunice has also recorded a video about this for the crowdfunder for the second Passionate Pantheon novel, Divine Burdens. Check it out!