Mark your calendars! On April 23, 2022, Eunice and Franklin will be presenting a live-stream of the start of a new Passionate Pantheon novel. If you’ve ever wanted to write a novel but don’t know how to get going, or you’ve wondered how co-authoring a book works, or if you’d just like to see the birth of a new book, show up! Bring questions! If you’re really really lucky, Eunice may pull out the chocolate eclairs! (Franklin is very onboard with this idea. Eunice is very onboard with chocolate in general.)

Ahem. Anyway…

With a new novel on the horizon, we recently took a step back to talk about the literary roots of the Passionate Pantheon. They’re unusual novels, to be sure, with feet in many different worlds.

By now many of you probably know the origin of The Brazen Altar: Eunice and Franklin met at an orgy in France in 2010. At another orgy in Lincolnshire in 2018, we decided to write together. Franklin wrote the opening paragraph of what would become The Brazen Altar on Eunice’s naked back, and thus the Passionate Pantheon was born.

But that doesn’t tell you a lot about why the books look and feel the way they do. Where did the inspiration come from? What influenced them stylistically? What inspired the world of the Passionate Pantheon, beyond Eunice’s sexy imagination (and inability to let a good wank alone, if you know what we mean)?

Terry Pratchett coined the term “white knowledge” (a play on “white noise”) to describe “the sort of stuff that fills up your brain without you really knowing where it came from.” In other words, the cultural and mythological equivalent to white noise that forms the largely unconscious background to every literary reference you catch, every little nerdy in-joke that thrills the heart when you notice it.

This is what we mean by white knowledge—the cultural myths and ways of viewing the world that float around your deepest subconscious, built over years and decades by the people and media around you, until it becomes hard to see the reality beyond the lens of story itself. We are the storytelling ape, and we tell ourselves all sorts of stories about how the world should work—how justice and morality works, how society works, how people work.

What we’re trying to do here is to be conscious of our own white knowledge. We’re trying, you might say, to pick out the individual threads that make up the tapestry of our own inner worlds.

Part of our aim in writing these stories, like all good sci-fi, is to wonder “What are we missing? What doesn’t have to work like that? What is the lens, and what is the deep dark forest where the wolves were hunted into extinction centuries ago?”

This, too, is a gift from Sir Terry Pratchett.

One early reader of The Brazen Altar said something along the lines of “it’s like the Culture, but even more hedonistic.” That’s not far off the mark; there’s a lot of Iain Banks’ Culture novels in the Passionate Pantheon, in the sense they’re both set in far-future societies that have transcended scarcity, where there’s no such thing as money (in the Culture, there’s a saying, “money is a sign of poverty”), where people live long lives (centuries, if they like), where there’s no disease or war, and where pleasure is considered good and proper as its own end. The Culture novels aren’t the only sci-fi series that has these elements, but there is a strong resemblance to the Culture’s specific flavor of these elements in the Passionate Pantheon.

There are differences, of course. We don’t see any spaceships in the Passionate Pantheon novels. In the universe of the Passionate Pantheon, faster-than-light travel isn’t a thing. The characters arrived on our world on slower-than-light generation ships, after a long fall through the inky void. The people who started the journey from Earth knew they would not live to see the journey’s end. They did it not for themselves, but for the sake of their descendents.

Iain Banks famously said he set most of the Culture novels outside the Culture because it’s hard to write a story where there’s no conflict and people live lives of peace and prosperity. We set our stories within our post-scarcity society, partly because we think there are plenty of stories to be told within the backdrop of peace and prosperity, but partly because there were topics that we could only really explore to their fullest in the context of that ability for our characters to make almost totally unconstrained choices.

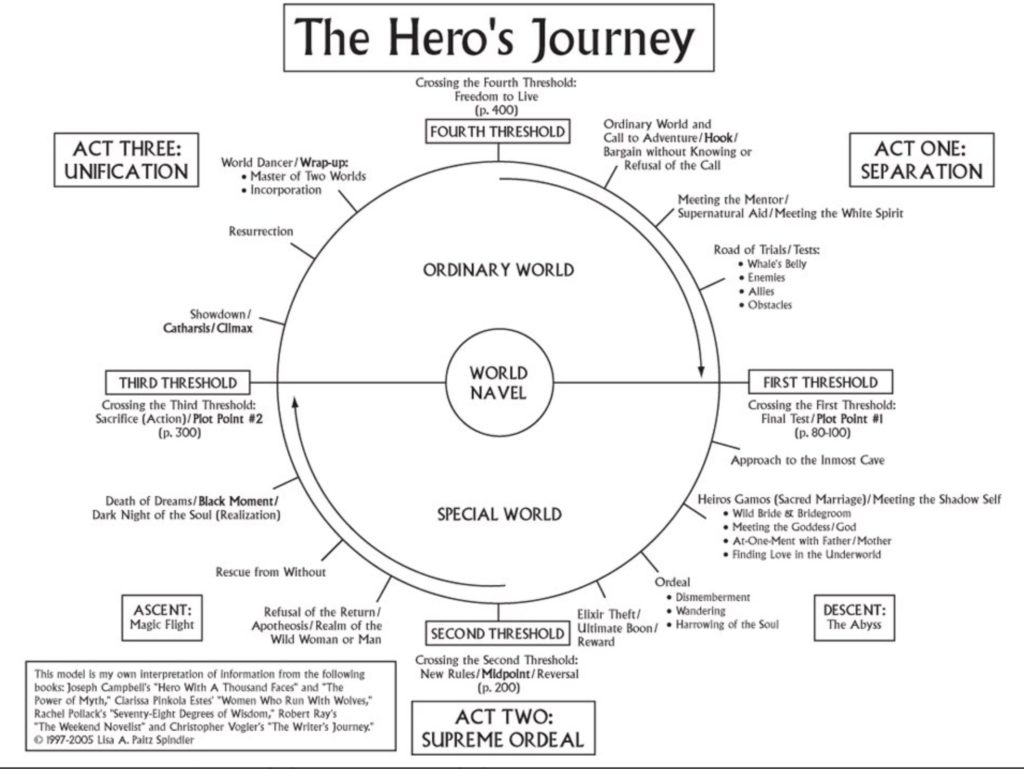

What you’ll notice, though, is that the Passionate Pantheon stories aren’t Campbell’s Hero’s Journey. They don’t follow the cycle of the classic monomyth—the sheriff or lone ranger doesn’t ride in from out of town to save the day, Neo doesn’t discover that all reality is a lie when he’s yanked out of his existence into the real world to take part in the unending secret war against the machines.

The stories we tell are more akin to coming of age stories, explorations of characters finding their place within and among the society they live in. The first three novels (The Brazen Altar, Divine Burdens, and The Hallowed Covenant) follow characters becoming Sacrifice to their chosen AI gods, reaching the highest level of prestige among their peers. The fourth novel, Unyielding Devotion, centers on characters who aren’t highly placed in their society, who don’t earn the recognition and admiration of their peers for attaining high status.

In a sense, though, the stories we tell really aren’t science fiction. Well, they are; they’re set in a City with molecular nanoassemblers, medical pods, radical longevity, antigravity float fields, shield generators, strong AI, and fusion power. Thing is, we’ll never discuss in the text how these things work; they’re all backdrops for the stories, since we both believe good stories are about people, not technology. (We know how it all works, of course, we’re just not telling you. Buy us some chocolate eclairs, though, and we might consider it!)

Rather, in many ways, the people of the City are a modernist reinterpretation of the fey from mythology…but the fey as they see themselves, from within their own society, not as they are seen by human outsiders. We’ve written about this before: the characters of the Passionate Pantheon are reinterpretations of the fey, humans seen through a glass darkly, an exploration of what we might become if we were granted the powers from those old fables.

In that sense, then the Passionate Pantheon stories draw upon the narrative archetypes of the old fairy stories—not the kinder, gentler fairy tales for children (well, the adult conception of children anyway—actual children love a bit of gore and blood), but the wild fey, the dangerous fey. The fey for whom names have power, beauty is a foundational virtue, a promise is a sacred thing (the upcoming novel The Hallowed Covenant explores in depth what happens if you break a promise in the City—or at least one of the Cities—and how the City handles transgression and wrongdoing without police or even a codified set of laws), and you and those around you will live for centuries.

So we use a setting that calls back to the Culture novels, with narrative structures that derive from ancient stories about the fey. But that’s not all you’ll find in the Passionate Pantheon gumbo!

We use the stories in the Passionate Pantheon, particularly the darker even-numbered books, to hold up a mirror to modern society. In that sense, the stories are a bit like the Discworld books (of which we’re both huge fans), though we don’t do it quite the same way Terry Pratchett does. (But then, who can?)

Our social commentary is far less text and far more subtext. We explore themes of consent and agency in a society which has inverted modern-day social taboos about sex and volence—where violence is casually accepted but sex is a forbidden topic in the real world, sex is a normalized part of social interaction in the Passionate Pantheon, but they regard violence with uneasy horror.

We use this inversion as a literary mirror to confront ideas about self, agency, consent, and coercion: why do people in the real world regard, say, sex work with a degree of horror they don’t apply to boxing, for instance? Why is it considered acceptable for people to sell access to their bodies to receive a beating, but not an orgasm?

Whilst we’d never try to compare ourselves to the inimitable Pterry, we do, like he did, use the Passionate Pantheon as a vehicle for looking at some things in the real world that make us go “hmm.”

Of course, in addition to these three major influences we mentioned here—the Culture novels, Discworld, and old fairy tales—there are a countless myriad of other elements and inspirations we didn’t mention that came before us and influenced the way we write. Hopefully we will also bequeath some small measure of the same to those who come after us. This is a cycle that could—no, will—continue as long as humans exist.

We draw inspiration from all over. No creator is an island. No literature stands alone; all stories draw on universalities of the human condition. There are endless ways to mix the gumbo, though, and this is our particular flavor. Not only that, it is the particular flavor that we, as writers in combination, and at this particular stage of our lives and our writing careers, have produced in this specific setting. If or when each of those elements changes, the flavor will change a little again. Every extra bit of knowledge or experience is another ingredient in the pot.

If you’re interested in writing, you too will have your own special pot, with your own unique, yet culturally flavored, style. We’d love to know what your influences are, if you’d like to share that with us.

We hope you’ll join us on April 23 as we start a new pot going. The fifth book will delve deep into parts of City life we haven’t explored yet, including family, childhood, and death. Come along with us! The writing is a fun ride.